First U.S. bird flu death reported in Louisiana after severe case of H5N1

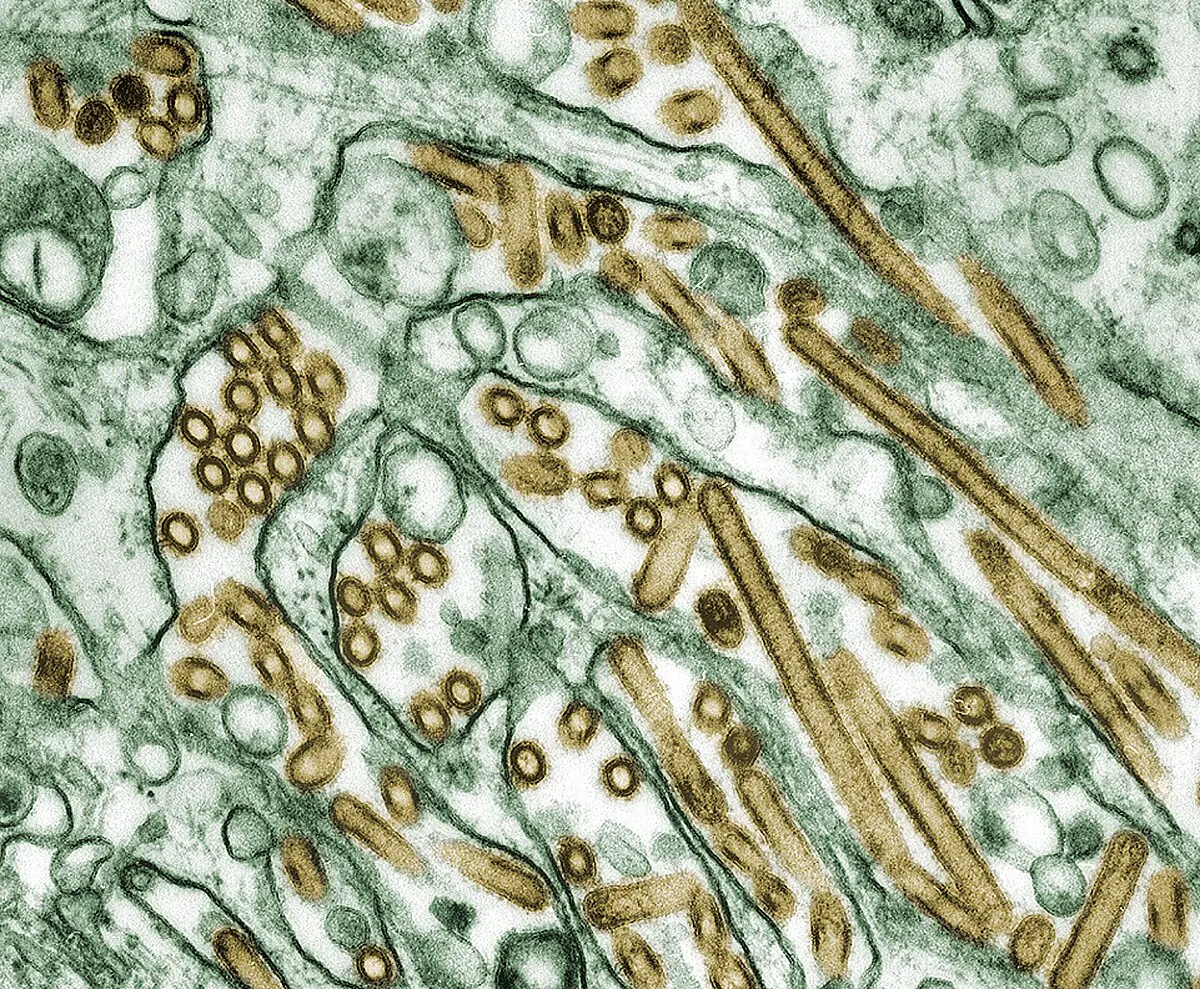

A Louisiana resident has died after being hospitalized with bird flu, the state's health department announced Monday, marking the first U.S. death from the H5N1 virus.

"The patient was over the age of 65 and was reported to have underlying medical conditions," Louisiana's health department said in a statement, saying that health officials still judge the public health risk from the virus as low for the general public.

The patient tested positive and developed severe illness after being exposed to wild birds and a personal backyard poultry flock that was infected with the virus, according to the health department. No other people were found to have been sickened by the virus in Louisiana.

"CDC has carefully studied the available information about the person who died in Louisiana and continues to assess that the risk to the general public remains low. Most importantly, no person-to-person transmission spread has been identified," the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said in a statement Monday.

H5N1 has been linked to at least seven other deaths from other countries in recent years. Since 2003, the World Health Organization has counted more than 400 deaths from the virus.

One other U.S. hospital patient tested positive for the virus last year in Missouri, though officials said that the person had not been admitted because of the virus. Instead, the patient was in the hospital being treated for other preexisting medical conditions.

The Louisiana patient was sickened by the D1.1 strain of the bird flu virus, genetic sequencing by the CDC determined last month.

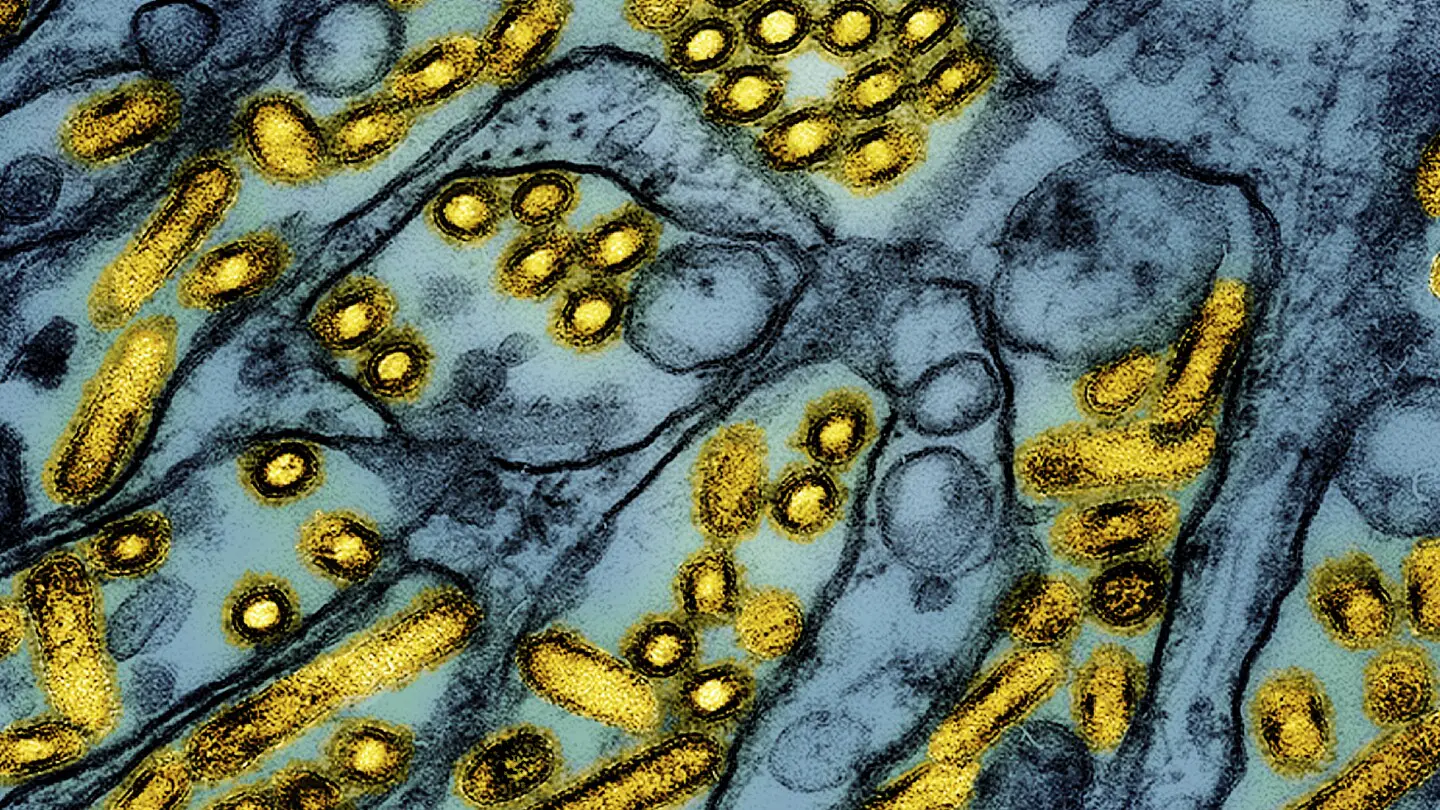

The patient's virus did have some rare and potentially worrying mutations, the sequencing revealed. Those genetic changes to the virus likely arose later during the person's infection, the CDC's investigation concluded, and were not found in the animals that likely infected them.

"Although concerning, and a reminder that A(H5N1) viruses can develop changes during the clinical course of a human infection, these changes would be more concerning if found in animal hosts or in early stages of infection," the CDC said.

The D1.1 strain is the same as the virus behind a severe illness of a 13-year-old girl who was hospitalized late last year in Canada.

Health authorities in the Canadian province of British Columbia said last year that they had been unable to identify the source of the infection, but did find that the virus sequence closely matched wild birds that were flying through the province in October.

This D1.1 strain of H5N1 bird flu is different from the B3.13 genotype which has been fueling this past year's unprecedented outbreak on dairy farms across the U.S.

Including the Louisiana case, the CDC tallies 66 reported human cases in the U.S. since last year from any of the H5 strains of bird flu.

Most of the human cases have been in workers who got sick with the B3.13 strain after working with infected cattle. None of those human cases have been hospitalized or have died from the virus.

The CDC has said there remains "no evidence of sustained human-to-human" spread of H5N1. There are some past outbreaks overseas where the agency says "limited" H5N1 transmission is suspected to have occurred within small clusters of people.

Wild birds or poultry have now tested positive for at least one of the H5N1 strains in every state. In November, Hawaii became the 50th state to report detecting an infected bird. Hundreds of cattle herds across at least 16 states have also tested positive for H5N1.

"While the current public health risk for the general public remains low, people who work with birds, poultry or cows, or have recreational exposure to them, are at higher risk. The best way to protect yourself and your family from H5N1 is to avoid sources of exposure," Louisiana's health department said.

Bird flu has led to a wide variety of symptoms during recent outbreaks, including common flu symptoms like cough and vomiting. Many have also had conjunctivitis or pink eye as their only symptom, which experts suspect is from contaminated milk from cows infected by bird flu being splashed onto workers.

Most of the U.S. cases have seen their symptoms resolve a median of four days after first getting sick. The majority were also treated with the antiviral oseltamivir, also known by the brand name Tamiflu, which may have helped to speed their recovery.

The hospitalized child in Canada initially had conjunctivitis and fever before later developing cough, vomiting and diarrhea. She was later intubated after respiratory failure.

U.S. records its first human bird flu death

The U.S. has recorded its first human death from bird flu, a grim milestone that comes as at least 67 cases have been recorded in the country.

The patient, who was over 65 and had underlying medical conditions, was hospitalized in Louisiana in December; the case was considered the country’s first severe human H5N1 infection.

The Louisiana Department of Health said the patient had been exposed to a combination of a backyard flock and wild birds.

“The Department expresses its deepest condolences to the patient’s family and friends as they mourn the loss of their loved one,” it said in a statement. “Due to patient confidentiality and respect for the family, this will be the final update about the patient.”

All but one of the human bird flu infections confirmed so far in the U.S. were diagnosed in the last 10 months, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Most cases have been relatively mild, with symptoms including pinkeye, coughs or sneezes.

The majority of the patients became sick after exposure to infected cattle or poultry. The Louisiana patient was the first case linked to exposure to a backyard flock.

Just two cases have involved patients who did not have known exposure to animals. One was a person in Missouri who was hospitalized with bird flu in September but recovered after being treated with antiviral medications. The other was a child in California who experienced mild symptoms in November.

The CDC maintains that the immediate risk to public health is low. Public health officials have not found any evidence that the virus has spread person-to-person, which would mark a dire step in bird flu's evolution.

“While tragic, a death from H5N1 bird flu in the United States is not unexpected because of the known potential for infection with these viruses to cause severe illness and death,” the agency said in a statement on Monday.

“There are no concerning virologic changes actively spreading in wild birds, poultry, or cows that would raise the risk to human health,” the statement added.

However, samples of the virus collected from the Louisiana patient showed signs of mutationsthat could make it more transmissible to humans, according to the agency.

The strain of bird flu behind the ongoing outbreak began spreading globally among wild birds and poultry in 2020. Since it took root in the U.S. in 2022, more than 130 million birds have been infected or culled. The virus has also spread to dairy cows and other mammals. More than 900 bird flu cases have been detected in cattle since March.

Rising transmission among animals increases the odds that humans could be exposed and that the virus could mutate in ways that could lead to a pandemic. Bird flu appears to spread efficiently on dairy farms, likely because cows shed the virus through their mammary glands, then infect other animals through their raw milk. The virus has also turned up in wastewater in several states, including in sites without dairy or poultry facilities.

For people concerned about bird flu risk, the CDC advises against drinking unpasteurized raw milk and suggests avoiding contact with sick or dead animals. Workers on poultry or dairy farms affected by H5N1 should wear personal protective equipment and monitor for symptoms.

The federal response to bird flu ramped up a month ago, when the U.S. Department of Agriculture ordered testing of the national milk supply, starting in six states. The Biden administration also set aside $306 million last week for additional surveillance, laboratory testing and medical research for bird flu.

But some experts have criticized the U.S.'s response for being too slow or limited.

“The Biden administration has been mishandling the outbreak in cattle for months, increasing the possibility of a dangerous, wider spread,” two former Food and Drug Administration officials wrote in an editorial in The Washington Post on Friday.

America’s first bird flu death reported in Louisiana

The first person to have a severe case of H5N1 bird flu in the United States has died, according to the Louisiana Department of Health. This is the first human death from bird flu in the US.

The person, who was over 65 and reportedly had underlying medical conditions, was hospitalized with the flu after exposure to a backyard flock of birds and to wild birds.

Louisiana health officials said that their investigation found no other human cases linked to this patient’s infection.

Flu experts have been warning that the H5N1 virus would bare its teeth as infections spread.

“We’ve been studying the family tree of this virus for 25 odd years, and this is probably the nastiest form of the virus that we’ve seen. So the fact that it finally did cause a fatal infection here is tragic but not surprising,” said Dr. Richard Webby, who directs the World Health Organization Collaborating Center for Studies on the Ecology of Influenza in Animals and Birds at St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital.

Since 2003, there have been roughly 900 human bird flu infections reported globally, and about half of those people have died, according to the World Health Organization. That would give the virus a 50% case fatality rate, making it extraordinarily lethal – but experts don’t actually think it kills half the people it infects.

Because severe cases are more likely to be reported than mild ones, mild illnesses probably aren’t being factored into that figure.

But even if the actual case fatality rate were 10 times lower – about 5% – it would still be a serious virus to contend with. The case fatality rate for the ancestral strain of Covid-19 was estimated to be around 2.6%, for example.

A recent study by scientists from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on the first 46 human cases of H5N1 in the US last year found that they were nearly all mild and, except one, happened after exposure to infected farm animals.

The Louisiana patient was infected with the D1.1 clade of the bird flu virus, a strain that is circulating in wild birds and poultry. It’s different from the variant that’s circulating in dairy cattle.

Scientists don’t know whether it is associated with more severe disease in people. D1.1 also infected a critically ill teenager who was hospitalized in Canada. The teen, a 13-year-old girl, received intensive care and recovered, but investigators don’t know how she was exposed.

D1.1 infections have also been identified in poultry farm workers in Washington. Those cases appear to have been milder.

The CDC reported in late December that a genetic analysis of the virus that infected the Louisiana patient found changes expected to enhance its ability to infect the upper airways of humans and help it to spread more easily from person to person. Those same changes were not seen in the birds the person had been exposed to, officials said, indicating that they had developed in the person after they were infected.

CDC officials are continuing to investigate the case by looking at the virus in “serial samples” or blood tests taken from the patient over time. That will give them more information about how the virus was evolving in the patient’s body.

“The evolution of the virus is concerning but highlights how we need to prevent each possible spillover infection to reduce the risk of onward transmission to others,” said Dr. Seema Lakdawala, a microbiologist and immunologist who studies influenza transmission at the Emory University School of Medicine.

In a statement Monday, the CDC called the death tragic but said that this single case had not raised the threat level from H5N1.

“CDC has carefully studied the available information about the person who died in Louisiana and continues to assess that the risk to the general public remains low. Most importantly, no person-to-person transmission spread has been identified,” according to the statement.

“Additionally, there are no concerning virologic changes actively spreading in wild birds, poultry, or cows that would raise the risk to human health,” the statement said.

While most people continue to have a low risk from bird flu, people who keep chickens and other birds in their backyards need to be cautious, as do workers on dairy and poultry farms, health officials said.

People who work with animals, or who have been in contact with sick or dead animals or their droppings, should watch for breathing problems and red eyes for 10 days after exposure. If they develop symptoms, they should tell their health care provider about their recent exposure.

Other ways to stay safe include:

Louisiana reports first bird flu-related death in US

Jan 6 (Reuters) - A U.S. patient who had been hospitalized with H5N1 bird flu has died, the Louisiana Department of Health said on Monday, marking the country's first reported human death from the virus.

The patient, who has not been identified, was hospitalized with the virus on Dec. 18 after exposure to a combination of backyard chickens and wild birds, Louisiana health officials had said.

The patient was over age 65 and had underlying medical conditions, officials said, putting the patient at higher risk for serious disease.

Nearly 70 people in the U.S. have contracted bird flu since April, most of them farmworkers, as the virus has circulated among poultry flocks and dairy herds, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Federal and state officials have said the risk to the general public remains low.

The ongoing bird flu outbreak, which began in poultry in 2022, has killed nearly 130 million wild and domestic poultry and has sickened 917 dairy herds, according to the CDC and the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

An analysis of the virus taken from the Louisiana patient showed it belongs to the D1.1 genotype - the same type that has recently been detected in wild birds and poultry in Washington State, as well as a recent severe case in a teen in British Columbia, Canada, according to the CDC.

It is different from the B3.13 genotype currently circulating in U.S. dairy cows, which has mostly been associated with mild symptoms in human cases including conjunctivitis, or pink eye.

The CDC said the risk to the general public remains low. Experts have been looking for signs that the virus is acquiring the ability to spread easily from person to person, but the CDC said there is no evidence of that.

People who work with birds, poultry, cows, or have recreational exposure to them, are at higher risk, Louisiana health officials said in a statement.

Worldwide, more than 950 human cases of bird flu have been reported to the World Health Organization, and about half have resulted in death.

"Though H5N1 cases in the U.S. have been uniformly mild, the virus does have the capacity to cause severe disease and death in certain cases," said Dr. Amesh Adalja, senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security.

Several experts said the death was concerning, but not surprising.

"This is a tragic reminder of what experts have been screaming for months, H5N1 is a deadly virus," said Jennifer Nuzzo, an epidemiologist and director of the Pandemic Center at Brown University's School of Public Health.

"I hate to have the death of somebody be a wake-up call," said Gail Hansen, a veterinary and public health consultant.

"But if that's what it takes, hopefully that will make people look at bird flu a little more carefully and say this really is a public health issue we need to be looking at more closely."

First US bird flu death is announced in Louisiana

NEW YORK (AP) — The first U.S. bird flu death has been reported — a person in Louisiana who had been hospitalized with severe respiratory symptoms.

State health officials announced the death on Monday, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed it was the nation’s first due to bird flu.

Health officials have said the person was older than 65, had underlying medical problems and had been in contact with sick and dead birds in a backyard flock. They also said a genetic analysis had suggested the bird flu virus had mutated inside the patient, which could have led to the more severe illness.

Few other details about the person have been disclosed.

Since March, 66 confirmed bird flu infections have been reported in the U.S., but previous illnesses have been mild and most have been detected among farmworkers exposed to sick poultry or dairy cows.

A bird flu death was not unexpected, virus experts said. There have been more than 950 confirmed bird flu infections globally since 2003, and more than 460 of those people died, according to the World Health Organization.

The bird flu virus “is a serious threat and it has historically been a deadly virus,” said Jennifer Nuzzo, director of the Pandemic Center at the Brown University School of Public Health. “This is just a tragic reminder of that.”

Nuzzo noted a Canadian teen became severely ill after being infected recently. Researchers are still trying to gauge the dangers of the current version of the virus and determine what causes it to hit some people harder than others, she said.

“Just because we have seen mild cases does not mean future cases will continue to be mild,” she added.

In a statement, CDC officials described the Louisiana death as tragic but also said “there are no concerning virologic changes actively spreading in wild birds, poultry or cows that would raise the risk to human health.”

In two of the recent U.S. cases — an adult in Missouri and a child in California — health officials have not determined how they caught the virus. The origin of the Louisiana person’s infection was not considered a mystery. But it was the first human case in the U.S. linked to exposure to backyard birds, according to the CDC.

Louisiana officials say they are not aware of any other cases in their state, and U.S. officials have said they do not have any evidence that the virus is spreading from person to person.

The H5N1 bird flu has been spreading widely among wild birds, poultry, cows and other animals. Its growing presence in the environment increases the chances that people will be exposed, and potentially catch it, officials have said.

Officials continue to urge people who have contact with sick or dead birds to take precautions, including wearing respiratory and eye protection and gloves when handling poultry.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

'Unprecedented': How bird flu became an animal pandemic

Bird flu is decimating wildlife around the world and is now spreading in cows. In the handful of human cases seen so far it has been extremely deadly.

The tips of Lineke Begeman's fingers are still numb from a gruelling mission. In March, the veterinary pathologist was part of an international expedition to Antarctica's Northern Weddell Sea, studying the spread of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI), the virus that has now encircled the globe, causing the disease known as bird flu.

Cutting into the frozen bodies of wild birds that the team collected, Begeman was able to help establish whether they had died from the disease. The conditions were harsh and the location remote, far from her usual base at the Erasmus Medical Centre in the Netherlands. But systematic monitoring like this could provide a vital warning for the rest of the world.

"If we don't study the extent of its spread now, then we can't let people know what the consequences are of having let it slip through our fingers when it began," Begeman tells BBC Future Planet. "I imagine the virus as an explorer going through the world, to new places and bird species, and we're following it along."

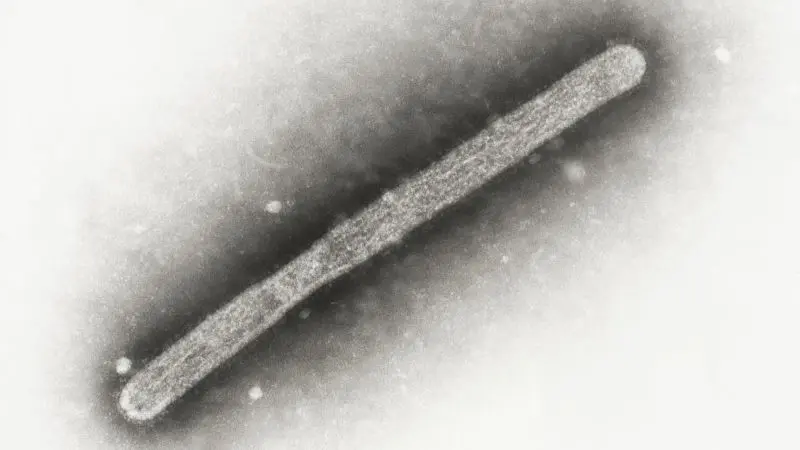

Relatively few people have caught the virus so far, but the H5N1 subtype has had a high mortality rate in those that do: more than 50% of people known to become infected have died. In March 2024, the US discovered its second case in humans, which was also the first instance of mammal-to-human transmission. By May 2024, the first death from a rare H5N2 subtype of the virus was reported in Mexico. Then in August, the US saw its first hospitalisation for H5 avian influenza with no known exposure to a sick animal.

Moreover, the impact on animals has already been devastating. Since it was first identified, the H5 strain of avian influenza and its variants have led to the slaughter of over half a billion farmed birds. Wild-bird deaths are estimated in the millions, with around 600,000 in South America since 2023 alone – and both numbers potentially far higher due to the difficulties of monitoring.

At least 26 species of mammals have also been infected. In Denmark, millions of mink were culled after bird flu spread through fur farms. In France, a captive bear was found to be infected, as have free-ranging bears in Canada. Among wild mammals, scavengers and marine mammals have been particularly badly hit. The virus has killed ten of thousands of seals and sea lions from Quebec down to Chile, Argentina and Peru - with concerns rising that it may be adapting to spread more easily between mammals and then back to birds.

In Antarctica's Northern Weddell Sea, Begeman and her colleagues sampled around 120 carcasses from different species, including several Antarctic fur seals. The virus was detected at four of the 10 sites they visited.

It was not the first time bird flu had been detected on this remote continent. That first case was a month prior, in February 2024. But theirs was the first confirmation from this particular region, and the first time, Begeman believes, that a multidisciplinary team had set out to systematically determine its Antarctic spread.

"The moment we found the first evidence of that destructive serial killer virus amidst such a bird-rich, pristine area, we realised what disaster is about to happen and it became sickening indeed," says Begeman.

Already the worst bird flu outbreak in wildlife on record, scientists like Begeman are now racing to track its journey – and so better understand how its further spread among humans might be stopped.

China's southern Guangdong region is a mosaic of lakes, rivers and wetlands. These watery habitats are well suited to aquatic birds, who are natural hosts for low pathogenic avian flu. And it was here, in 1996, that a farmed goose became the world's first bird to be diagnosed with a new, highly pathogenic strain of the virus, known as H5N1.

The categorisation of bird flu as low or highly pathogenic was established in relation only to chickens, not to other bird (or mammal) species. But whereas low-path avian influenza is non-fatal in wild birds and only causes mild disease in chickens, in poultry, low path strains can mutate into fatal high-path ones, causing severe illness and often death.

It should be no surprise that the highly pathogenic virus's first case was detected on a poultry farm, says Thijs Kuiken, a comparative pathologist at Erasmus University Medical Centre in the Netherlands. "Highly pathogenic avian influenza is typically a poultry disease, which doesn't occur in the wild. What's unusual now, is this particular type has spilled into wild birds and this has allowed it to spread worldwide."

Although wild birds have now helped the virus reach far beyond China, "people are the real problem", Kuiken warns. And in particular, humanity's ever-rising demand for farmed meat.

When this outbreak started in 1996, there were around 14.7 billion poultry birds in the world, mostly chickens. Now there's double that number. "Biomass-wise, poultry currently forms over 70% of all avian biomass worldwide," Kuiken notes.

If the current poultry farming trends don't change, then "other highly infectious pathogens will continue to spread into the few wild birds remaining," Kuiken says. House finches, for instance, are proving particularly susceptible to a bacterial poultry disease, Mycoplasma gallisepticum. Virulent strains of Newcastle disease are also crossing over into multiple species, including parrots and macaws. "HPAI [high-pathogenic bird flu] is only one threat."

By 2005-06 the virus had spilled over into wild birds and was travelling as far as Europe, Africa and the Middle East, but it was disappearing in these populations after only a few months – likely a combination of not spreading well enough in wild birds, not surviving well enough in water, and some birds developing immunity, says Kuiken. This helped to limit the extent of its impact and its ability to further mutate.

That relative containment changed in 2020, however, when a new strain of H5N1 emerged. Though it's not known exactly why, the strain could maintain itself in wild bird populations year-round. Now able to spread during springtime when birds gather in high densities to breed, the virus rapidly became endemic in wild bird populations.

In late 2021, the virus arrived in the New World via Canada's eastern Newfoundland province. A black-backed gull, found sick in a pond, was taken to a wildlife rehabilitation centre where it died the following day. It was later found to be positive for H5N1. Days after its death, a poultry farm started reporting increased mortality rates and autopsies also confirmed presence of the virus.

The fact there was no evidence this farm had imported poultry from Europe helped to confirm scientists' theories that wild birds' migration routes are the key long-distance carrier, explains Kuiken. There have been some exceptions, however, such as the transport of infected turkeys from the UK to Europe.

By 2022, birds in colonies from the UK to Israel were dying in their thousands. In October 2022, the virus was detected in wild birds on the west coast of Peru and Chile. After travelling down the coast, it then returned up the east, spreading to the Falkland Islands and South Georgia – the stepping stones to the Antarctic.

Along this route, the virus has diverged to infect a wide variety of mammals – including 21 species in the US alone. And with such cross-over, the opportunity for both human contact and mammal-to-mammal spread has increased.

By 16 April 2024, HPAI was confirmed in dairy cows on 26 farms in the US, from Texas to Michigan. Some of these may have been infected through wild birds, but other cases have been connected to cows' long-distance transport.

In December, the number of cases among cattle in the US had surged, with more than 800 farms in 16 states affected. Sporadic infections have been detected in a wide range of other mammals in the US, including mountain lions, skunks, dolphins, polar bears, domestic cats, mice and foxes. Meanwhile, an H5N1 virus strain was detected in two pigs on a farm in Oregon in October. The animals had been mixed with poultry on the farm.

But farms can create conditions that allow disease to spread more easily, offering new pathways for adaptation. "Wild birds can transmit the virus, but domestic farms can amplify it," says Gregorio Torres, head of the science department at the intergovernmental body the World Organisation for Animal Health, of the need for farmers to be especially cautious. "It's like avoiding getting into a packed metro when you're already sick."

One bright spot is that birds in New Zealand and Australia have so far been spared. The countries are part of the East Asian-Australian migration route, but their visiting birds are mostly shorebirds or waders, rather than more-susceptible waterfowl like ducks or geese, Kuiken notes.

The current outbreak of H5N1 bird flu has also hopped species numerous times to infect various mammals, including humans. So far, however, the virus is not thought to have evolved or mutated sufficiently to jump easily between the mammals it infects – though September 2024 the US confirmed its first case with no known exposure to animals.

The very first human cases were reported in Hong Kong in 1997, and the global spread of the virus was relatively slow: during its first 13 years only 800 people were reported infected, with poultry and slaughterhouse workers at greatest risk.

Contact with sick birds – or with their droppings, saliva or feathers – was found to be the biggest risk factor for contracting the virus, though the exact mechanism by which the virus jumps species is not yet known.

In March 2024, a new, rare form of the virus was detected in cattle. By April, a farm worker in Texas became the second human in the US to ever contract H5N1 – in what it thought to be the first instance of mammal-to-human transmission.

Cow-to-cow transfer has since been confirmed, with "anything that comes in contact with unpasteurised milk" potentially spreading the disease, according to the US Department of Agriculture.

Scientists cannot yet predict if bird flu will become the next global human pandemic, says TorresYet what is clear is that the disease is here to stay – and we need to be prepared. "Every time there's a jump between species, it's a signal of potential increased risk," says Torres. "That's why we're quickly acting to try to understand and anticipate its evolution."

Torres adds: "The worst case is it adapts to mammals, with a greater risk of human-to-human transmission."

Diana Bell, a conservation biologist at the University of East Anglia in the UK, says when people ask her what the next pandemic in humans will be, bird flu immediately comes to mind. "I say we already have a pandemic in animals and birds [a panzootic]."

So can bird flu be stopped? Not in wildlife, experts say; transmission is too hard to prevent. But there are still things we can do to limit the harm to both wild and farmed mammals – as well as humans.

Dead wild birds should be left untouched and reported to authorities, experts encourage. Meanwhile, farms are also being urged to deploy biosecurity measures, from covering waste to reporting illnesses. And the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) is pressing to ensure compensation schemes are in place for all farms that undergo mandatory culling.

More controversial is the question of vaccinating poultry. Preventative vaccination in the most high-risk species and areas has been shown to minimise outbreaks, and WOAH advises this. Some nations, like China, already vaccinate routinely, but others have been more reluctant. Not least due to trade barriers which restrict the import of poultry and eggs from vaccinated flocks.

"When you vaccinate poultry, it's harder to demonstrate absence of disease and early-detect its presence. So it's posing a challenge for international trade, as everyone wants trade to be safe," says Torres. But better surveillance can offset this risk, he adds.

Future outbreaks of HPAI could also be controlled and even prevented via reforms to global meat production, Kuiken says. A more sweeping approach could include a cap on the global poultry population size and more equitable consumption – Europe currently eats twice as much meat as global health authorities advise, Kuiken notes. (Read BBC Future's article on sustainable sources of protein.)

HPAI is already a pandemic in global wildlife. "With this virus, the conservation impact is already unprecedented," says Marcela Uhart, a veterinarian at UC Davis. "It's on a scale we've never seen: in terms of the number of species and regions affected, we've never seen anything like it."

Of particular concern in Uhart's home nation of Argentina, has been the virus's spread in wild mammals. Her study into its adaptation to such mammals showed the same virus was nearly identical in fur seals and sea lions, and that many of the adaptations they detected were also present in a human case in Chile. "For all we know it could already be further adapting to spread between mammals – and we need to detect that as quickly as possible."

And while this is worrying in terms of the future impact on humans, it is also already proving devastating to other mammals: more than 17,000 elephant seals are thought to have died from the virus during the 2023 breeding season, including 70% of all the season's pups. Since no one knows how many adults went on to die at sea from the virus, Uhart and her colleagues are now waiting apprehensively for the creatures return from the ocean this spring. If enough pregnant females come back, there will be capacity for recovery, Urhart says. If not, or if the virus hits again this year, "the impact could be major".

"We're all feeling very anxious about this," Urhart says. There is pressure to keep monitoring the population-level impact on wildlife, though she says there is inadequate funding. "Everything we're doing now is on a shoestring," she says.

But the need to keep monitoring is key. "The removal of these species from the food chain could disrupt the whole ecosystem," Urhart says. "A lot of what's coming into the future is just so uncertain."

Reducing other pressures on wildlife could aid their survival as H5N1 becomes a new pressure on bird and mammal species. Climate change, habitat loss, bycatch in fisheries, overfishing, invasive species and pollution – via everything from plastics to pesticides – are all reducing global biodiversity. Easing those human pressures could help give populations infected by HPAI more scope to recover, says Richard Phillips, a seabird ecologist at the British Antarctic Survey.

Phillips' work on albatrosses has shown that fishing vessels that use mitigation methods (such as not discarding fish at the same time as trawling, and using bird-scaring lines) can reduce the amount of seabird bycatch. With bird flu already hitting the vulnerable wandering albatross, Phillips fears the species' outlook is "bleak" unless the threat from fisheries is addressed.

In the meantime, scientists will continue to track HPAI's spread in wild populations, and find new ways to do so.

Begeman's expedition, for the first time, set up an entire testing laboratory on an Antarctic-bound ship. Wildlife biologists would scout sampling areas on foot for dead birds, while others would sample apparently healthy animals, she explains. Her role was to cut into the carcasses to investigate, shoo-ing away curious sheathbills as they went. "We were really like detectives, able to get to sites where people had never visited."

The hope is that by collecting this information from the most far-flung places on the planet, scientists can inform the choices we make closer to home. For Kuiken, policy changes to reduce risk in the poultry industry are high on his list. Meanwhile, vaccination, preventative measures and conservation could all be crucial to help birds and mammals through this outbreak.

--

This story was updated on 19/12/2024 with information about new cases of H5N1 in the United States.

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.