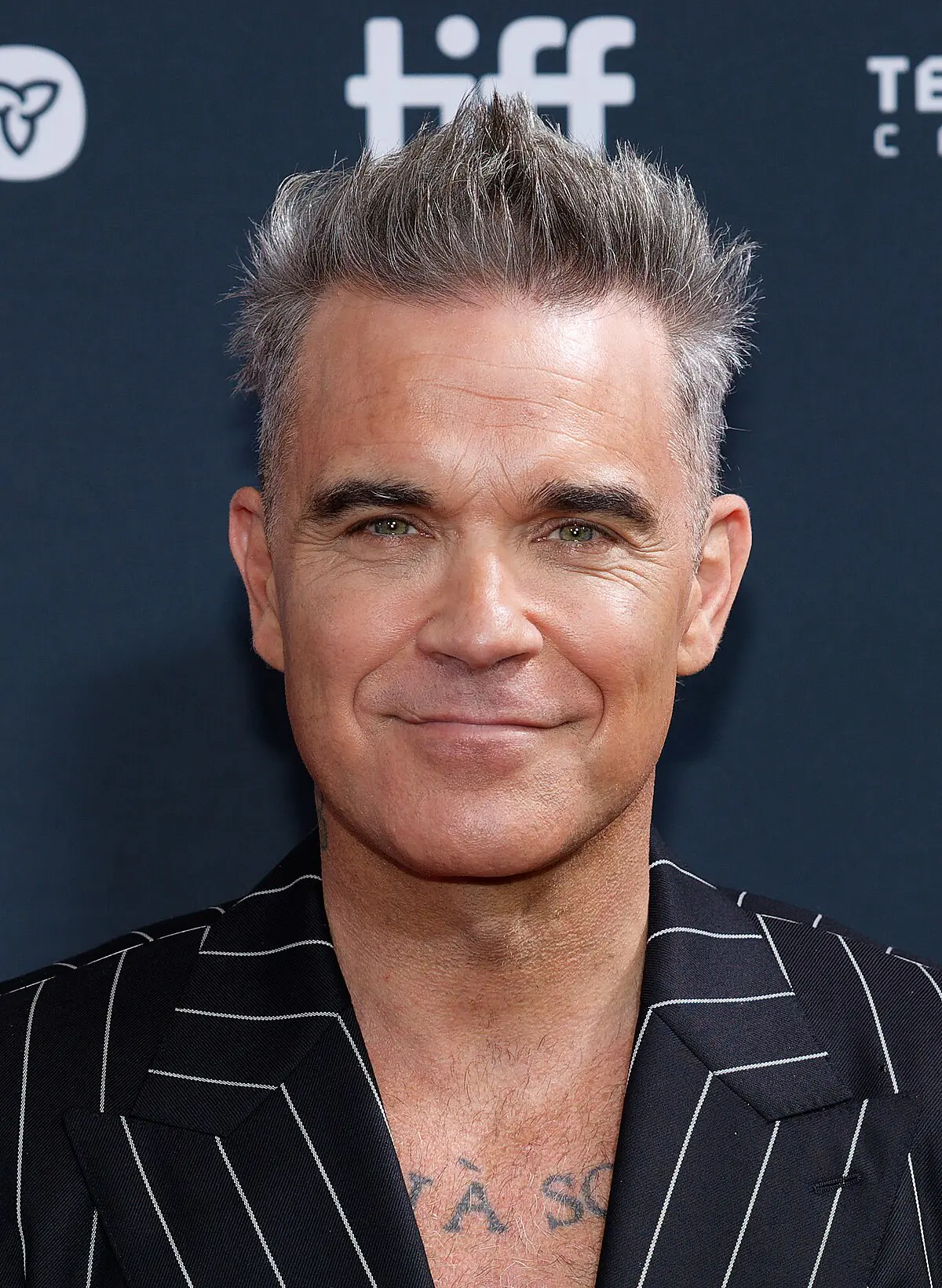

How new Robbie Williams biopic Better Man lays bare the terror of fame – by making its hero a CGI chimp

A new film about the tumultuous career of UK boy-band sensation turned solo star Robbie Williams depicts him as an ape. Directed by the maker of The Greatest Showman, it's a revelatory look at the highs and lows of pop stardom.

Fame is a relentlessly potent force in pop culture. Its pulse-racing allure – and its bone-crushing pitfalls – have continually inspired songs, from Bowie to Billie Eilish, and fuelled films from technicolour romance to gritty life stories and psych-horror. Better Man, a new big-budget biopic of British boyband sensation turned solo artist Robbie Williams, offers a first-hand view of the fame circus, with an unusual twist: its leading star is portrayed as a CGI chimp (played by actor Jonno Davies, using motion-capture VFX). Williams is not a household name everywhere – as he is in the UK – but nevertheless the film offers a fascinating insight into stardom either way. For Australian director Michael Gracey (The Greatest Showman), this deeply surreal scenario remains natural territory: "Ultimately, the film seeks to tell the story I am always chasing: the pursuit of an impossible dream," he says in the film's production notes.

For Williams, there is a characteristically snappy logic to his filmic guise. "There is a surrender to the machinery of the industry that requires you to be a robot or a monkey," he explains, also in the production notes. "I chose to be a monkey."

Better Man introduces us, via Williams's signature tune Let Me Entertain You, to a born performer ("I came out of the womb with jazz hands – which was very painful for my mum," jokes Williams's narrative voiceover). There's evidently something different about young Robert, but the CGI is so beguilingly expressive, it also feels entirely plausible that this wide-eyed boy chimp is immersed in a human world: crooning along to Sinatra with his dad (Steve Pemberton), listening to stories from his grandma (a wonderfully cuddly Alison Steadman). Williams's drive for stardom is evident, but so are his deep-rooted self-doubts, and fear of being a "nobody".

The turn of the 1990s brings a key change; at 16, Williams was the youngest member of Take That: a Manchester pop quintet fashioned by manager Nigel Martin-Smith after the massive success of Stateside heartthrobs New Kids On The Block. Take That were not an overnight smash; the film depicts their chaotic inception (with Williams's voiceover noting that each member made £180 each in the first 18 months) – but the band grafted their way to becoming a genuine phenomenon, dominating the charts and mass teenage dreams, with Williams's loveably cheeky persona fronting their breakthrough hits.

Better Man serves choreographed set-pieces that blend British pop culture detail and Busby Berkeley-style extravaganza; a euphoric group performance of Williams's track Rock DJ captures the way that pop stardom can feel superhuman. We're swiftly reminded of its precariousness, though, via Williams's dizzying descents into self-destruction and depression, and his departure from Take That. Each time he performs onstage, he sees demon doppelgangers glowering back at him within the crowds – a terror that intensifies, even as he establishes a record-breaking solo career.

Williams has always been candid about his flaws and battles with addiction and excess – it's as though he can't stop picking at his scars, via song lyrics, soundbites or documentaries, including the tour film Nobody Someday (2002) and a Netflix series (2023), as well as several books by his official biographer, Chris Heath. Yet there is something especially visceral about Better Man's dramatisation; Williams's simian form heightens the florid weirdness of his music industry experiences – and also takes the brutal edge off some of the bleakest points in his story. The film never takes on a glib "jukebox musical" approach, where hit tunes are shoehorned into the narrative; instead, Better Man's soundtrack re-contextualises several of Robbie's biggest songs (Feel, sung by his childhood self; Come Undone; She's The One, reimagined as a duet as he falls in love with fellow pop star Nicole Appleton), in a way that feels revelatory. Robbie has always been an extravagant showman, but a sense of intimacy – whether it's his yearning for affection and acceptance, or his spiky self-critique – seems surprisingly amplified here.

Williams is an undeniably magnetic presence, onscreen or in the flesh. I have met him in person on two occasions; the first time, I was doing a work experience placement at British pop magazine Smash Hits in the early-'90s, when Williams bounced into the office with his Take That bandmate Jason Orange. They looked at me, quizzically; I was a teenage girl, their target demographic. Dazzled by their sexy aura of fame, I was too shy to do anything but stare back.

More like this:

• The 2024 drinking song that became a huge US hit

• End of an Era: The show that took over the world

• Should there be a ban on teenage popstars?

A couple of decades later, there was a more talkative encounter; I was interviewing Williams for Metro newspaper, where I was Music Editor. He was releasing his ninth album Take The Crown, and he was still restlessly ambitious. "I'm obsessed… with pop music, being a pop star, being successful, not being a has-been," he told me. He spoke about the quest for the perfect pop song, and described fixating on negative YouTube comments, even though they were hugely outweighed by positive posts.

Better Man is not only a Robbie Williams biopic. It is a snapshot of the 1990s: a period where the music business was booming, and the fame phenomenon rose to a feverish crescendo. Pop culture was arguably never the same again. Band managers might have been visionary, but they were also often ruthlessly controlling and directing every aspect of young artists' lives, from their punishing work schedules to their diets and personal relationships.

Music consultant, manager and writer Alex Kadis was formerly features editor of Smash Hits, and worked closely with members of Take That for years. "The managers were very competitive with each other – which made the bands and fanbases competitive," she tells the BBC. "I think that's part of the intensity of the '90s. And I think it's the first time I really became aware of emotional marketing; suddenly, there was this sense that artists could have a deep connectivity with their audiences – they weren't just plugging a product, but themselves as human beings."

This could prove to be a raw exchange. As a young journalist, I interviewed the infamous pop Svengali Tom Watkins (who had managed boy bands Bros and East 17, as well as the Pet Shop Boys); he was both fascinating and utterly formidable. "We're selling sex," barked Watkins.

Given the sacrifices associated with fame – the loss of privacy and autonomy; the culture shock when artists suddenly find themselves outside the bubble of a band – the messy meltdowns depicted in Better Man seem quite inevitable. Kadis recalls when Williams quit Take That in 1995. "At that point, he was like a man who was suffering from PTSD," she says. "He wasn’t sleeping; he was starting to take a lot of drugs; he didn't know who he was anymore. I think the '90s bled those pop stars dry. They had to keep on feeding their audience and playing a character."

Kadis likens the pop fame trajectory to a runaway train ("It really depends on what carriage you managed to jump on for a bit"). For all of its exhilarating highs, its route is also clearly traumatic; the tragic death of Liam Payne earlier this year is another indictment of the pressures that young artists are expected to endure. Williams recently appeared in a BBC series, Boybands Forever, where he spoke some home truths: "Nobody goes through that level of fame and comes out completely sane". Significantly, the end credits of Better Man include a pointer to the 988 Lifeline Suicide and Crisis support service.

Better Man's narrative blasts through many classic elements: A Star Is Born-style ambitious adventure; a nightmarish descent; a father-son bonding story. Ultimately, it is also a redemption tale, which concludes in the early 21st Century, although anyone who has followed Williams's career – or the music industry at large – will know, the show is far from over. When I interviewed Williams, I asked him what superpower his pop fame had given him: "To get on stage, face your fear and the responsibility that everyone relies on you for their livelihood. I take my hat off to me," he replied, laughing. "Because it's terrifying and exhilarating."

Better Man is released in the UK and Australia on 26 December, and has a limited release in the US on 25 December.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.

For more Culture stories from the BBC, follow us on FacebookX and Instagram