America’s first bird flu death reported in Louisiana

The first person to have a severe case of H5N1 bird flu in the United States has died, according to the Louisiana Department of Health. This is the first human death from bird flu in the US.

The person, who was over 65 and reportedly had underlying medical conditions, was hospitalized with the flu after exposure to a backyard flock of birds and to wild birds.

Louisiana health officials said that their investigation found no other human cases linked to this patient’s infection.

Flu experts have been warning that the H5N1 virus would bare its teeth as infections spread.

“We’ve been studying the family tree of this virus for 25 odd years, and this is probably the nastiest form of the virus that we’ve seen. So the fact that it finally did cause a fatal infection here is tragic but not surprising,” said Dr. Richard Webby, who directs the World Health Organization Collaborating Center for Studies on the Ecology of Influenza in Animals and Birds at St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital.

Since 2003, there have been roughly 900 human bird flu infections reported globally, and about half of those people have died, according to the World Health Organization. That would give the virus a 50% case fatality rate, making it extraordinarily lethal – but experts don’t actually think it kills half the people it infects.

Because severe cases are more likely to be reported than mild ones, mild illnesses probably aren’t being factored into that figure.

But even if the actual case fatality rate were 10 times lower – about 5% – it would still be a serious virus to contend with. The case fatality rate for the ancestral strain of Covid-19 was estimated to be around 2.6%, for example.

A recent study by scientists from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on the first 46 human cases of H5N1 in the US last year found that they were nearly all mild and, except one, happened after exposure to infected farm animals.

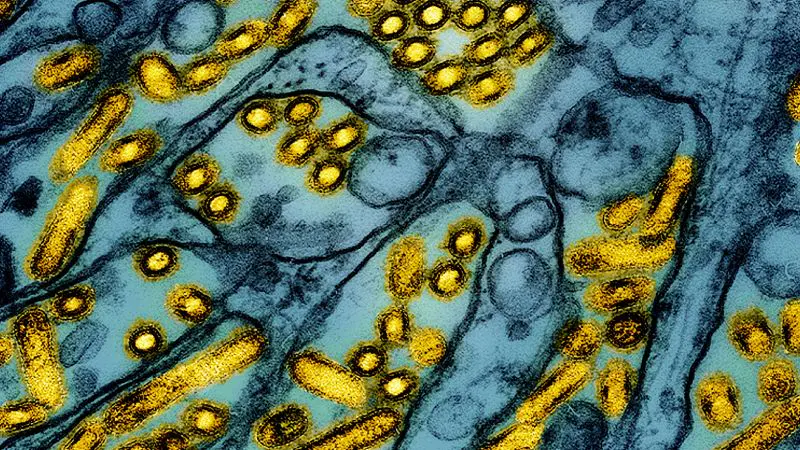

The Louisiana patient was infected with the D1.1 clade of the bird flu virus, a strain that is circulating in wild birds and poultry. It’s different from the variant that’s circulating in dairy cattle.

Scientists don’t know whether it is associated with more severe disease in people. D1.1 also infected a critically ill teenager who was hospitalized in Canada. The teen, a 13-year-old girl, received intensive care and recovered, but investigators don’t know how she was exposed.

D1.1 infections have also been identified in poultry farm workers in Washington. Those cases appear to have been milder.

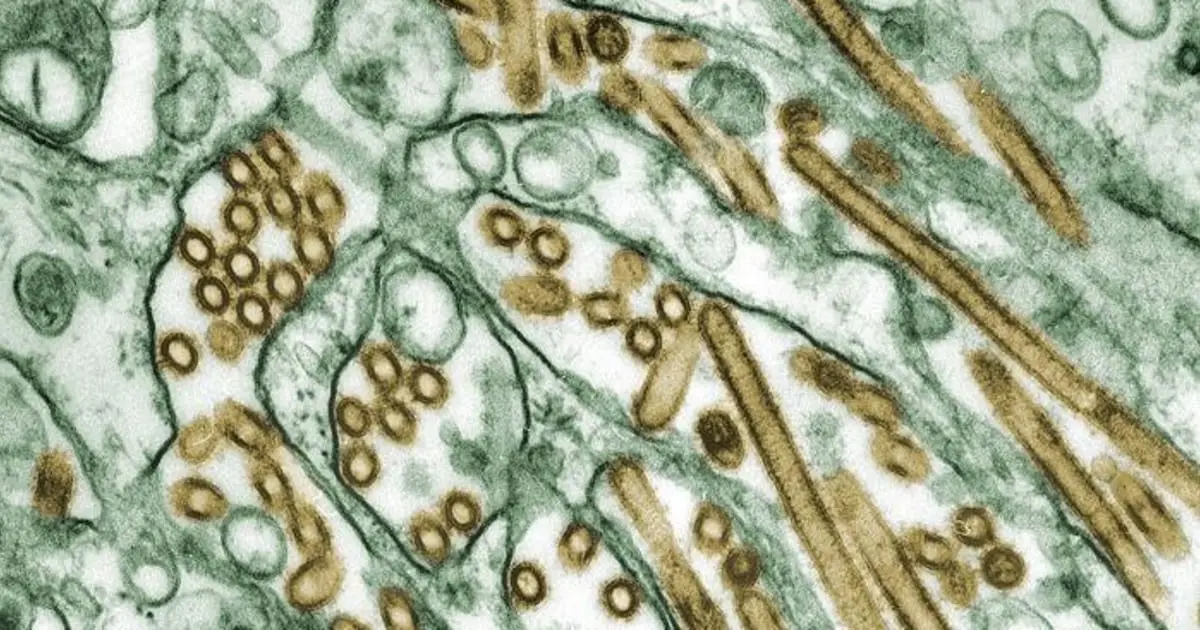

The CDC reported in late December that a genetic analysis of the virus that infected the Louisiana patient found changes expected to enhance its ability to infect the upper airways of humans and help it to spread more easily from person to person. Those same changes were not seen in the birds the person had been exposed to, officials said, indicating that they had developed in the person after they were infected.

CDC officials are continuing to investigate the case by looking at the virus in “serial samples” or blood tests taken from the patient over time. That will give them more information about how the virus was evolving in the patient’s body.

“The evolution of the virus is concerning but highlights how we need to prevent each possible spillover infection to reduce the risk of onward transmission to others,” said Dr. Seema Lakdawala, a microbiologist and immunologist who studies influenza transmission at the Emory University School of Medicine.

In a statement Monday, the CDC called the death tragic but said that this single case had not raised the threat level from H5N1.

“CDC has carefully studied the available information about the person who died in Louisiana and continues to assess that the risk to the general public remains low. Most importantly, no person-to-person transmission spread has been identified,” according to the statement.

“Additionally, there are no concerning virologic changes actively spreading in wild birds, poultry, or cows that would raise the risk to human health,” the statement said.

While most people continue to have a low risk from bird flu, people who keep chickens and other birds in their backyards need to be cautious, as do workers on dairy and poultry farms, health officials said.

People who work with animals, or who have been in contact with sick or dead animals or their droppings, should watch for breathing problems and red eyes for 10 days after exposure. If they develop symptoms, they should tell their health care provider about their recent exposure.

Other ways to stay safe include:

First U.S. bird flu death reported in Louisiana after severe case of H5N1

A Louisiana resident has died after being hospitalized with bird flu, the state's health department announced Monday, marking the first U.S. death from the H5N1 virus.

"The patient was over the age of 65 and was reported to have underlying medical conditions," Louisiana's health department said in a statement, saying that health officials still judge the public health risk from the virus as low for the general public.

The patient tested positive and developed severe illness after being exposed to wild birds and a personal backyard poultry flock that was infected with the virus, according to the health department. No other people were found to have been sickened by the virus in Louisiana.

"CDC has carefully studied the available information about the person who died in Louisiana and continues to assess that the risk to the general public remains low. Most importantly, no person-to-person transmission spread has been identified," the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said in a statement Monday.

H5N1 has been linked to at least seven other deaths from other countries in recent years. Since 2003, the World Health Organization has counted more than 400 deaths from the virus.

One other U.S. hospital patient tested positive for the virus last year in Missouri, though officials said that the person had not been admitted because of the virus. Instead, the patient was in the hospital being treated for other preexisting medical conditions.

The Louisiana patient was sickened by the D1.1 strain of the bird flu virus, genetic sequencing by the CDC determined last month.

The patient's virus did have some rare and potentially worrying mutations, the sequencing revealed. Those genetic changes to the virus likely arose later during the person's infection, the CDC's investigation concluded, and were not found in the animals that likely infected them.

"Although concerning, and a reminder that A(H5N1) viruses can develop changes during the clinical course of a human infection, these changes would be more concerning if found in animal hosts or in early stages of infection," the CDC said.

The D1.1 strain is the same as the virus behind a severe illness of a 13-year-old girl who was hospitalized late last year in Canada.

Health authorities in the Canadian province of British Columbia said last year that they had been unable to identify the source of the infection, but did find that the virus sequence closely matched wild birds that were flying through the province in October.

This D1.1 strain of H5N1 bird flu is different from the B3.13 genotype which has been fueling this past year's unprecedented outbreak on dairy farms across the U.S.

Including the Louisiana case, the CDC tallies 66 reported human cases in the U.S. since last year from any of the H5 strains of bird flu.

Most of the human cases have been in workers who got sick with the B3.13 strain after working with infected cattle. None of those human cases have been hospitalized or have died from the virus.

The CDC has said there remains "no evidence of sustained human-to-human" spread of H5N1. There are some past outbreaks overseas where the agency says "limited" H5N1 transmission is suspected to have occurred within small clusters of people.

Wild birds or poultry have now tested positive for at least one of the H5N1 strains in every state. In November, Hawaii became the 50th state to report detecting an infected bird. Hundreds of cattle herds across at least 16 states have also tested positive for H5N1.

"While the current public health risk for the general public remains low, people who work with birds, poultry or cows, or have recreational exposure to them, are at higher risk. The best way to protect yourself and your family from H5N1 is to avoid sources of exposure," Louisiana's health department said.

Bird flu has led to a wide variety of symptoms during recent outbreaks, including common flu symptoms like cough and vomiting. Many have also had conjunctivitis or pink eye as their only symptom, which experts suspect is from contaminated milk from cows infected by bird flu being splashed onto workers.

Most of the U.S. cases have seen their symptoms resolve a median of four days after first getting sick. The majority were also treated with the antiviral oseltamivir, also known by the brand name Tamiflu, which may have helped to speed their recovery.

The hospitalized child in Canada initially had conjunctivitis and fever before later developing cough, vomiting and diarrhea. She was later intubated after respiratory failure.

We ‘have our head in the sand’: Health experts warn US isn’t reacting fast enough to threat of bird flu

The US hasn’t learned lessons from the Covid-19 pandemic that it could use to mitigate the threat of pathogens like H5N1 bird flu that keep showing signs of their own pandemic potential, health experts told CNN Friday.

“We kind of have our head in the sand about how widespread this is from the zoonotic standpoint, from the animal-to-human standpoint,” Dr. Deborah Birx, the White House Coronavirus Response Coordinator under President Donald Trump, said on “CNN Newsroom” with Pamela Brown.

Birx called for much wider-spread testing of farm workers who make up the majority of identified cases in the US, noting the country is heading into an even higher-risk period as seasonal flu begins to circulate. That raises the possibility a person could get infected with both seasonal flu and H5N1 and the viruses could swap gene segments, Birx said, giving the bird flu virus more tools to better infect humans, a phenomenon known as reassortment.

A spokesperson for the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention pushed back on Friday, telling CNN in a statement that the “comments about avian flu (H5N1) testing are out of date, misleading and inaccurate.”

“Despite data indicating that asymptomatic infections are rare, CDC changed its recommendations back in November to widen the testing net to include testing asymptomatic people with high-risk exposure to avian flu, and during the summer, it instructed hospitals to continue subtyping flu viruses as part of the nationwide monitoring effort, instead of the normal ramping down of surveillance at the end of flu season,” the spokesperson said.

“The result: more than 70,000 specimens have been tested, looking for novel flu viruses; more than 10,000 people exposed to avian flu have been monitored for symptoms, and 540 people have been tested specifically for H5N1,” the spokesperson continued. “Additionally, CDC partnerships with commercial labs mean that H5N1 tests are now available to doctor’s offices around the country, significantly increasing testing capacity.”

The CDC added it has a seasonal flu vaccination campaign underway for farm workers in states with infected herds to help protect them from seasonal flu and to reduce the chance of reassortment with the H5N1 virus.

The agency has also said there’s currently no human-to-human spread of H5N1. But risks continue to emerge that the virus could evolve to more easily infect people.

The CDC reported Thursday that a genetic analysis of samples from the patient in Louisiana recently hospitalized with the country’s first severe case of H5N1 show the virus likely mutated in the patient to become potentially more transmissible to humans, but there’s no evidence the virus has been passed to anyone else.

The patient was likely infected after having contact with sick and dead birds in a backyard flock, the CDC said earlier this month. In its Thursday analysis, the agency said the mutations it identified in samples taken during the patient’s hospitalization weren’t found in the birds, suggesting they aren’t in the virus widely circulating in wildlife.

The mutations, similar to ones observed in a hospitalized patient in British Columbia, Canada, may make it easier for the virus to bind to cell receptors in humans’ upper respiratory tracts, the CDC said.

“The changes observed were likely generated by replication of this virus in the patient with advanced disease rather than primarily transmitted at the time of infection,” the agency said. “Although concerning, and a reminder that A(H5N1) viruses can develop changes during the clinical course of a human infection, these changes would be more concerning if found in animal hosts or in early stages of infection… when these changes might be more likely to facilitate spread to close contacts.”

The CDC emphasized the risk to the general public has not changed and remains low, but said the detection of the genetic mutations “underscores the importance of ongoing genomic surveillance in people and animals, containment of avian influenza A(H5) outbreaks in dairy cattle and poultry, and prevention measures among people with exposure to infected animals or environments.”

The analysis found no changes associated with markers that might mean antiviral drugs wouldn’t work as well against the virus, the CDC added, and noted the samples are closely related to strains that could be used to make vaccines, if needed.

The sequences also didn’t show changes in genes associated with adaptation to mammals, the CDC found. The patient was infected with a strain known as D1.1 that’s closely related to viruses circulating in wild birds and poultry in the U.S.; another strain known as B3.13 has been spreading widely in dairy cows and hasn’t been found to cause severe disease in humans in the U.S.

“While this sounds like good news, the H5N1 situation remains grim,” Dr. Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada, posted on Bluesky on Thursday.

“There has been an explosion of human cases,” she said. “We don’t know what combination of mutations would lead to a pandemic H5N1 virus… but the more humans are infected, the more chances a pandemic virus will emerge.”

The CDC has confirmed 65 cases of H5N1 bird flu in humans in 2024. Of those, 39 were associated with dairy herds and 23 with poultry farms and culling operations. For two cases, the source of exposure is unknown. The severe case in the Louisiana is the only one associated with backyard flocks.

Dr. Paul Offit, a vaccine scientist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, noted the CDC said the mutations “may” enable to the virus to bind better to cell receptors in humans’ upper respiratory tracts, not that they clearly do.

“I’d like to see clear evidence… that it binds well,” Offit told CNN Friday. “That hasn’t happened yet.”

“And more importantly,” Offit added, “there’s not the clinical relevance that you see human-to-human spread.”

The spread among animals like cows, though, has some health experts on high alert. Since the virus was first found in cattle in March, outbreaks have been detected in herds in 16 states.

This month the US Department of Agriculture began a national milk testing program to track the spread of the virus through dairy cattle, and the agency has thus far brought on 13 states that account for almost half of the country’s dairy production.

The program requires that raw milk samples be collected before the pasteurization process and shared with USDA for testing.

Government agencies say pasteurization inactivates the virus, making pasteurized milk safe to drink. The Food and Drug Administration and other health agencies warn consumers not to drink raw milk, not just because of the risk of H5N1 but also E. coli, salmonella and listeria.

That the H5N1 virus has already spread so rapidly among cattle, though, suggests “the USDA has basically dropped the ball, big-time,” said Dr. Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, in an interview with CNN Friday. “I think it was out of fear to protect the industry. And they thought it was going to burn out, and it didn’t.”

Osterholm also said the US and others around the world should have done more to examine lessons from the Covid-19 pandemic, and to accelerate work improving flu vaccines.

And, he noted, “you’ve got the new administration coming and saying they’re going to do in infectious diseases [research] for the next eight years,” referring to comments made by President Trump’s nominee to lead the US Department of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.

Osterholm said his risk assessment for H5N1 hasn’t changed as a result of the Louisiana findings this week, but that he’s always concerned about the threat pathogens like the bird flu virus pose.

“The pandemic clock is ticking,” Osterholm said. “We just don’t know what time it is.”

First US patient dies from H5N1: Will the bird flu become a pandemic?

A patient who'd been hospitalized in Louisiana with severe illness from H5N1 bird flu has died — the first human death from this type of avian influenza in the U.S., the Louisiana Department of Health announced on Monday, Jan. 6.

The person, whose identity has not been released, was over the age of 65 and had underlying medical conditions, the statement noted. The patient contracted H5N1 "after exposure to a combination of a non-commercial backyard flock and wild birds," the department said.

An extensive public health investigation found no other H5N1 cases nor evidence of person-to-person transmission.

While the state health department said the risk to the public remains low, the death is raising concern over whether the bird flu could lead to another pandemic or lockdown.

H5N1 has infected dozens of people in the U.S. and spread to 10 states and Canada this year.

California has declared a state of emergency over the spread of the virus in its dairy cows.

There hasn't been any person-to-person transmission of bird flu and the current public health risk is low, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention emphasizes.

But a single mutation of the virus strain now widely infecting dairy cattle could allow it to spread in humans and "could be an indicator of human pandemic risk," according to research published in December in the journal Science.

"The longer this virus circulates unchecked, the higher the likelihood it will acquire the mutations needed to cause a pandemic," Dr. Les Sims, a veterinary expert in Asia, told the American Veterinary Medical Association.

"We need to act urgently to prevent this scenario."

A genetic analysis of samples from the patient who died in Louisiana showed mutations that may make it easier to spread to people, the CDC reported in late December.

But a “sporadic case” of severe H5N1 bird flu illness is not unexpected, the CDC said in a news release.

"Previously, the majority of cases of H5N1 in the United States presented with mild illness, such as conjunctivitis, and mild respiratory symptoms and fully recovered," Dr. Demetre Daskalakis, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said during a media briefing on Dec. 18.

"It's notable that this is the first human case of H5N1 associated with a backyard or noncommercial flock."

Investigators believe exposure to the virus happened on the Louisiana patient's property, Daskalakis added. He declined to comment about the person's symptoms.

Dr. Peter Chin-Hong, an infectious disease physician at UCSF Health, said he was very concerned when news about the severe case in Louisiana was first announced in December.

"I'm not saying this is a cause for panic right now. But in the medium-term, I think all the signs are pointing to the temperature rising with bird flu in terms of its potential impact on humans," Chin-Hong told NBC News.

Almost all human bird flu patients in the U.S. have had contact with infected animals and when doctors analyzed 45 of those cases, they found all the patients had mild illness that lasted for a few days, according to a study published in The New England Journal of Medicine in late December.

When it came to symptoms, 93% of the infected people had conjunctivitis, 49% had a fever and 36% had respiratory issues.

Most patients received oseltamivir, an antiviral medication also known as Tamiflu.

New details have emerged about a Canadian teen — that country’s first bird flu patient — who was left in critical condition after contracting H5N1 last fall.

The 13-year-old girl, who has obesity and a history of mild asthma, first came to an emergency room in British Columbia in early November with conjunctivitis (pink eye) in both eyes and a fever, according to a case report published with her family’s permission in The New England Journal of Medicine at the end of December.

She was sent home, but then developed a cough, vomiting and diarrhea, and returned to the emergency room three days later in respiratory distress.

The girl was admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit at British Columbia Children’s Hospital with respiratory failure, pneumonia, acute kidney injury and other problems.

She developed acute respiratory distress syndrome — a life-threatening lung injury — and had to be intubated and placed on a form of life support.

The young patient received three antiviral medications and other therapy. As she improved, her breathing tube was removed at the end of November.

The girl is no longer infectious and no longer requires supplemental oxygen, according to additional information posted by The New England Journal of Medicine.

It’s still unknown how she was exposed to bird flu.

The H5N1 virus “can cause severe human illness,” the doctors and experts who authored the case report wrote.

“Evidence for changes to HA [a protein in the virus] that may increase binding to human airway receptors is worrisome.”

Outside experts were concerned, too.

“If you look at how severe this infection was, I think it’s pretty fair to say that this is a terrible virus,” Dr. Isaac Bogoch, an infectious disease specialist at Toronto General Hospital, told CBC News.

California has announced a recall of raw milk after the virus was found in some products from Fresno’s Raw Farm, LLC. Another recall covers raw milk from Valley Milk Simply Bottled of Stanislaus County.

Raw milk, which is not pasteurized, can expose people to germs and lead to serious health risks, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has warned.

Consumers don’t realize the raw milk they buy is not from a single cow, but pooled from many cows, says Dr. Ian Lipkin, an expert on emerging viral threats.

“If one cow in that group has H5N1, then it gets distributed to many, many more people,” Lipkin, professor of epidemiology at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, tells TODAY.com. “It’s not a good situation.”

Drinking or accidentally inhaling droplets from raw milk containing bird flu virus may lead to illness, California health officials warn. So can touching your face after touching the contaminated milk.

Pasteurized milk is safe to drink because pasteurization kills the bird flu virus and other germs, the experts emphasize.

The state is home to 37 human cases of bird flu, or more than half of the country’s total, according to the CDC. None are linked to raw milk.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture has ordered testing of milk for the virus, requiring that raw milk samples nationwide be collected and shared with the agency.

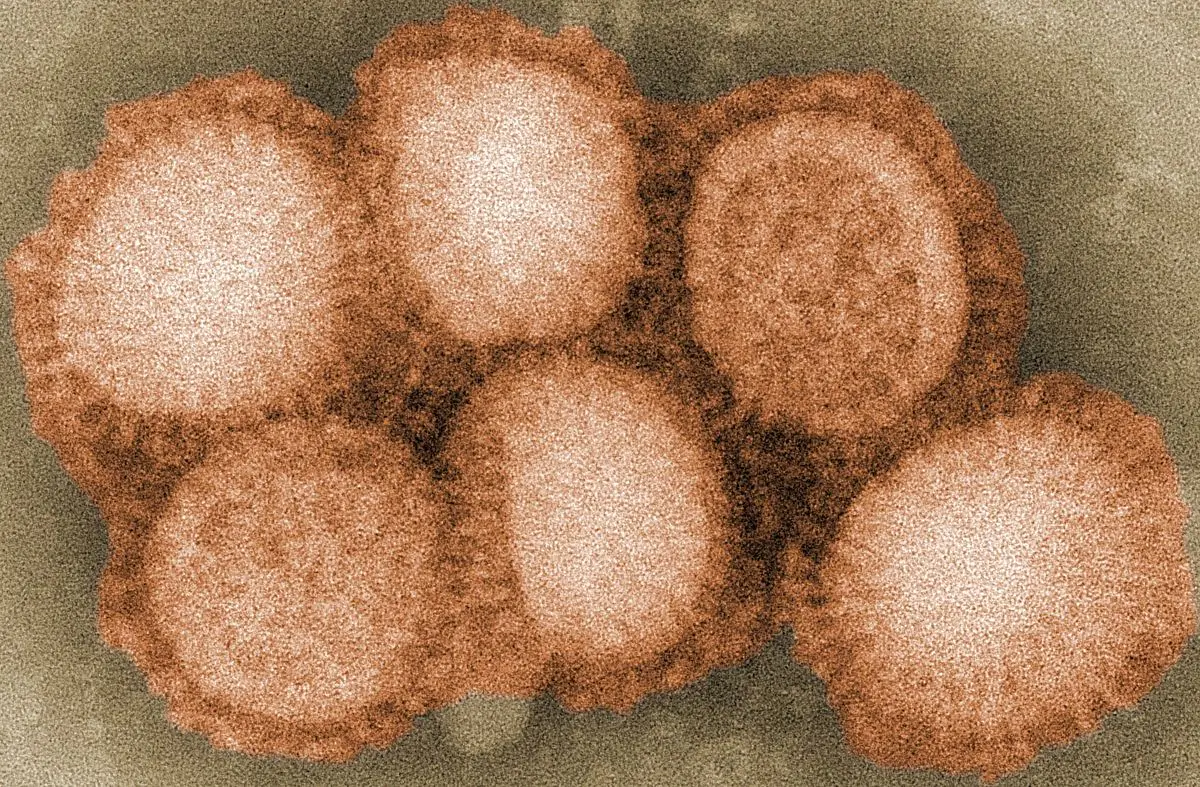

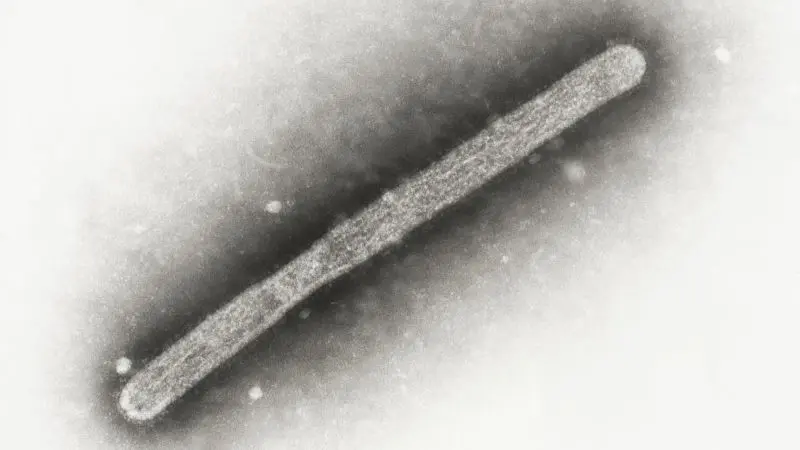

Like people, birds can get the flu, and the avian influenza viruses that make birds sick can sometimes infect other animals like cows and, rarely, people, the National Library of Medicine explains.

H5 is one family of bird flu viruses. It has caused widespread flu in wild birds worldwide and is causing outbreaks in poultry and U.S. dairy cows, the CDC notes. Some farm workers exposed to those animals have also gotten sick.

H5 has nine subtypes, including H5N1, the strain responsible for the recent illnesses.

Could bird flu cause the next pandemic? Here’s what to know about symptoms, how to protect yourself and more.

There have been 66 confirmed human cases in 10 states in the U.S. since the 2024 outbreak, according to the CDC.

They’ve been reported in:

Probable cases have also been reported in Arizona and Delaware, though the CDC was unable to confirm the presence of H5N1 in those samples in its laboratory.

Almost all U.S. patients had contact with infected cattle, poultry, backyard flocks, wild birds or other animals.

But two cases in North America are getting particular attention because it’s not known how they were exposed to the virus: the teenager in Canada and a person in Missouri.

There’s been no confirmed person-to-person spread.

“We do have an outbreak of human infections of H5N1,” says Dr. Amesh Adalja, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security and a spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

The current public health risk from H5 bird flu is low, the CDC says. Its flu monitoring systems currently show no signs of unusual flu activity in people, including the H5N1 virus, or any unusual flu-related trends in emergency department visits.

But the agency is “watching the situation carefully” — as are experts in the field.

Lipkin calls it an important health concern.

“Emerging infectious diseases are unpredictable. If you told me 20 years ago that we were going to have major problems with coronaviruses, I wouldn’t have predicted that,” Lipkin says.

“So nobody knows what’s going to happen with this particular flu.”

Human infection with bird flu can happen when the virus gets into a person’s eyes, nose or mouth, or is inhaled, according to the CDC. The illness can range from mild to severe and can be deadly.

Human H5N1 cases in the U.S. have been relatively mild, perhaps because people are mostly getting infected through their eyes, Adalja notes.

It might happen when a dairy worker is milking an infected cow and gets squirted in the face with the milk, for example.

“You’re getting infected from the eyes rather through the respiratory route,” Adalja tells TODAY.com. That may be “less risky than respiratory inhalation” of the virus, he adds, when it can go to the lungs.

No, the World Health Organization doesn’t currently categorize the bird flu outbreak as a global health emergency. Outbreaks that do fall into this category include COVID-19, cholera, dengue, Marburg virus and mpox.

The state of California recently declared a state of emergency over bird flu.

Experts say it’s unlikely this particular strain of bird flu would lead to a pandemic because it doesn’t have the ability to spread efficiently between people.

H5N1 has been infecting humans since 1997, so it’s had time to evolve, but still doesn’t easily jump from person to person, Adalja points out.

“I don’t think that this is the highest-risk bird flu strain,” he says. “You can’t say the risk is zero. But of the bird flu viruses, it’s lower risk.”

Lipkin had a similar take.

“Nobody ever wants to say never because you can be wrong,” he cautions. “Could this virus evolve to become more transmissible? Yes. Has it done so thus far? No. Do I personally think it’s going to be responsible for the next pandemic? No. Could it be? Yes.”

Since there are many different avian influenza strains, one of them may be able to cause a pandemic in the future, Adalja adds.

The bird flu strain he’s more worried about as a pandemic risk is H7N9, which was first reported in humans in China in 2013 and expanded to more than 1,500 people by 2017. This virus also doesn’t spread easily from person to person, but when people do get infected, most become severely ill, the World Health Organization warns.

The most recent human H7N9 virus infection was reported in China in 2019, according to the CDC.

A lockdown due to bird flu is not likely for this strain, since H5N1 isn’t posing a threat to the general public, both experts say.

If that were to change, people should realize lockdowns, like those during COVID-19, are not the “go-to measure” for an infectious disease emergency, Adalja says, calling them “very blunt tools.”

Instead, proactive measures — such as more aggressive testing of farm animals — will allow health officials to be much more precise when it comes to stopping the spread of infection, he notes.

When it comes to lockdowns, there’s also the question of how far authorities are willing to go.

“If H5N1 were to become a major health problem, we would have to talk about (containment),” Lipkin says. “But I don’t think that this incoming administration is going to be amenable to that.”

It’s oseltamivir, also known as Tamiflu, the same antiviral medication used for ordinary cases of flu.

It’s important to start that drug as soon as possible after symptoms start for it to have an impact, Lipkin says. Some close contacts of people who’ve been infected with H5N1 have also received the drug as a precautionary measure to prevent infection.

Four vaccine candidates for dairy cows have been approved for field trials, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

In poultry, four potential bird flu vaccines began to be tested in 2023, Reuters reported.

When it comes to humans, the CDC says the U.S. government is developing vaccines against H5N1 viruses “in case they are needed.”

The agency adds it has H5 candidate vaccine viruses that could be used to produce a vaccine for people, and preliminary analysis shows “they are expected to provide good protection” against H5N1.

There are also some vaccines in the strategic national stockpile that are closely — if not exactly — matched to this particular strain of bird flu, Adalja says.

“There are efforts to make more updated vaccines. But there is no widespread vaccination program being initiated against H5N1 at this time in the U.S.,” he notes.

In the summer of 2024, Finland became the first country in the world to offer bird flu vaccinations for people at risk of exposure, including workers at fur and poultry farms.

Finland bought vaccines for 10,000 people, each requiring two injections, Reuters reported.

In December 2024, the United Kingdom announced it had secured more than 5 million doses of human H5 influenza vaccine. The purchase will “boost the country’s resilience in the event of a possible H5 influenza pandemic,” the UK Health Security Agency said in a statement.

Bird flu in humans can cause no symptoms, or anywhere from mild to severe symptoms, according to the CDC. Most people who have been infected with bird flu have reported mild symptoms, such as eye infections and flu-like symptoms, according to Yale Medicine.

The CDC lists the following bird flu symptoms:

Yes, bird flu can be deadly.

The mortality rate of bird flu in humans, based on the roughly 900 confirmed people infected with the virus between 2003 and 2024, is about 50%, according to Yale Medicine.

However, it's likely that many more people have been infected without knowing it because they had no or mild symptoms, so the mortality rate could be much lower than 50%. And the mortality rate would likely drop even further if treatment and vaccines were made more widely available, should human-to-human spread start to occur.

There are several ways the bird flu virus can spread from animals to people, according to the CDC:

The people most at risk for H5N1 bird flu are dairy and poultry workers who might be around infected animals, Adalja says. They should wear personal protective equipment while working on farms affected by the virus, the CDC advises.

When it comes to the general public, “don’t consume raw milk, full stop” since H5N1 is viable in it, Lipkin says. Pasteurized milk can eliminate the risk of infection, he notes.

Properly cooked chicken is safe to eat, but wash your hands with soap and water after handling raw chicken, he adds.

It might be wise to skip petting zoos or events where you can learn how to milk a cow, Adalja adds.

Avoid direct contact with sick or dead wild birds, poultry and other animals, the CDC advises.